This chapter reviews the health and welfare impacts of air pollution in Europe. Although air pollution has decreased in most European countries over the past two decades, it remains above WHO guidelines in most countries, particularly in some large Central and Eastern European cities. This has serious consequences on people’s health and mortality.

Why it matters and how the health sector can reduce its burden

Air pollution is the main environmental risk factor for health in Europe and around the world. It has substantial health, economic and welfare consequences, including ill-health and greater premature mortality, increased health care costs, as well as reduced labour productivity and economic output in some sectors (e.g. agriculture and forestry sectors). The main sources of air pollution arise from the burning of fossil fuels in energy production, transport and households, and from some industrial and agricultural activities.

Depending on the methods of estimation, between 168 000 and 346 000 premature deaths across all EU member states in 2018 can be attributed to exposure to outdoor air pollution in the form of fine particles (PM2.5) alone. This represented 4% to 7% of all deaths in 2018. In addition, hundreds of thousands of people develop various illnesses associated with air pollution, leading to a loss of about 3.9 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) annually in the European Union.

While most European countries have substantially reduced their emissions of various air pollutants since 2005, most EU member states are still at risk of failing to fulfill their 2030 national emission reduction commitments unless additional measures are taken. A key element of the European Green Deal, announced in December 2019, is the zeropollution ambition for a toxic-free environment. A proposed zero-pollution action plan for air, water and soil will be announced for 2021. The EU recovery plan from the

COVID‑19 crisis, approved by the European Council in July 2020, aims to promote a green recovery by integrating environmental considerations into the recovery process.

This plan should also promote the achievement of national emission reduction commitments.

The health and economic burden of air pollution in Europe

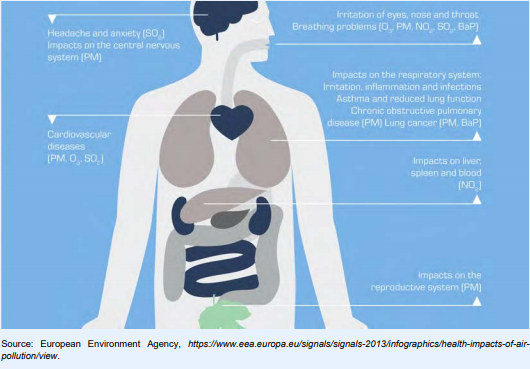

Air pollution causes different health problems, particularly respiratory and cardiovascular

diseases. Different air pollutants can affect different parts of the body (see figure). The greatest health

damage from air pollution is caused by chronic exposure to particulate matter, in particular to fine

particulate matter (PM2.5) which increases the risk of heart diseases, stroke, lung cancer and many

respiratory diseases including asthma, bronchitis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and respiratory infections. Exposure to air pollutants can take place both in outdoor (ambient) and indoor (household) environments.

In Europe, the impact on population health from exposure to outdoor air pollutants is much greater compared to that from indoor air pollutants.

Due to its impact on respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, emerging evidence suggests that increased long-term exposure to air pollution (notably PM2.5) increases the risk of severe COVID‑19

complications. In general, having pre-existing conditions linked to exposure to air pollutants

appears to make people more vulnerable to the effects of COVID‑19.

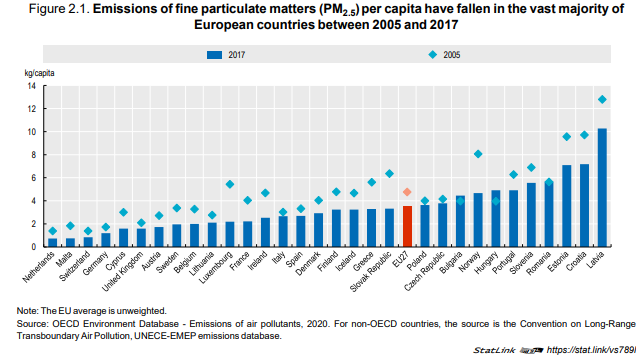

Since 2005, most European countries have made progress in reducing air pollution and notably

PM2.5 emissions (Figure 2.1), following the provisions included in the 2008 Ambient Air Quality

Directive and the more recent adoption of the EU Directive on National Emission reduction

Commitments (NEC) of certain air pollutants in 2016. On average across EU countries, emissions of

PM2.5 have reduced by over 25% between 2005 and 2017. These reductions reflect mainly

improvements in combustion processes in both industry and residential heating, a decrease in the use

of coal in the energy mix, and lower emissions from transport and to a lesser degree from agriculture.

However, this progress is not reflected in public opinion polls that show that most people believe that

air quality has deteriorated.

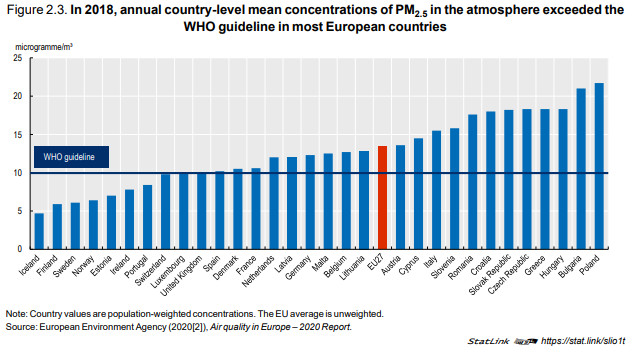

Reductions in emissions have led to reductions in (population-weighted) concentrations and,

therefore, reductions in population exposure to PM2.5 in most EU countries. Nonetheless, in 21 out of

31 European countries, the annual concentrations of PM2.5 exceeded the 10 microgrammes/m3

values recommended by the WHO Air Quality Guidelines in 2018. This is particularly the case in many

Central and Eastern European countries, mainly because of greater reliance on fossil fuels and other

dirty energy sources for heating and other purposes. Northern European countries have the lowest

levels of population exposure, generally well below the WHO guideline value for PM2.5 (Figure 2.3).

Between 168 000 and 346 000 people across all EU countries died prematurely in 2018 from diseases attributable to outdoor air pollution (PM2.5), according to the most recent estimates from the Global Burden of Disease study. This study provides information about differences in sources and methods that result in different estimates of the mortality attributed to air pollution.

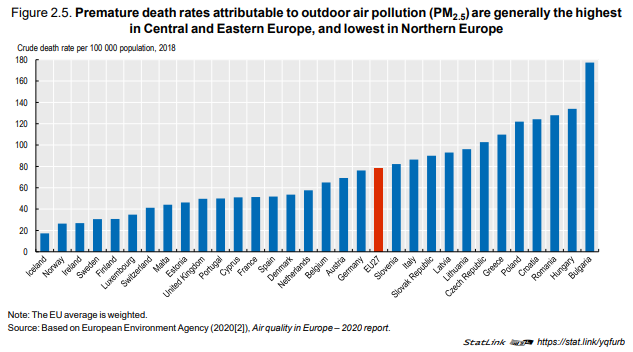

Premature death rates attributable to air pollution (PM2.5) were the highest in 2018 in Central and

Eastern European countries, reaching up to between 120‑180 deaths per 100 000 population in

Bulgaria, Hungary, Poland, Romania and Croatia. Deaths were the lowest in Nordic countries, with

rates about six times lower at 20‑30 deaths per 100 000 population (Figure 2.5).

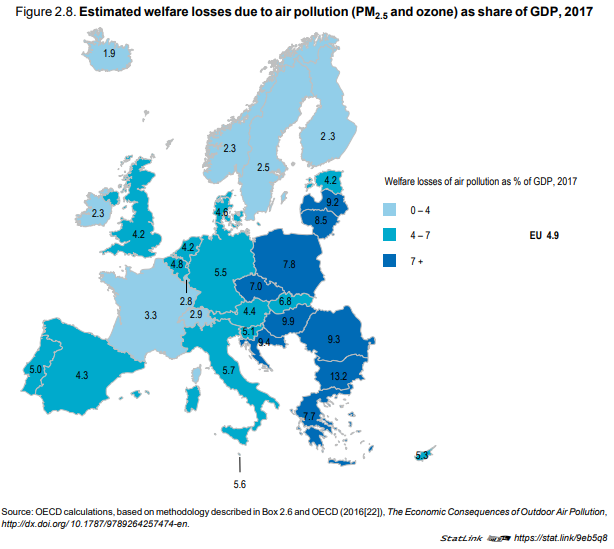

The serious health consequences of air pollution result in large welfare losses because of greater mortality and morbidity (lower quality of life due to ill-health), greater health spending care costs to treat related conditions, and reduced labour productivity arising from greater absences from work due to illness. The estimates have been updated to 2017 based on the assumption that the share of each cost category has remained constant in recent years. The estimates relate to the impact of PM2.5 (both outdoor and indoor) and ground-level ozone.

Welfare losses related to the lower quality of life of people living with illnesses that can be attributed to air pollution accounted for about 8% of total welfare losses, which is equivalent to about EUR 48 billion across all EU countries. Greater health care costs related to air pollution represented about 2.5% of total welfare losses, equivalent to about EUR 15 billion across EU countries. Finally, the labour productivity losses from lost working days due to illnesses related to air pollution accounted for the remaining 2% of welfare losses, equivalent to about EUR 11 billion across EU countries.

Taken together, the overall welfare losses of these air pollutants amounted to about

EUR 600 billion in 2017, equivalent to 4.9% of the EU GDP. As a share of GDP, the estimated welfare

losses related to air pollution were highest in Central and Eastern European countries (reaching

over 9% of GDP in Bulgaria, Croatia, Hungary, Latvia and Romania), and lowest in Nordic countries

(except Denmark), Ireland and Luxembourg (less than 3% of GDP) (Figure 2.8). These variations

mainly reflect differences in the burden of premature mortality due to air pollution, the main driver of

welfare loss estimates.

The main challenges to reducing the heavy impact of air pollution on people’s health and welfare consist of further reducing the emissions of air pollutants at all levels (local, regional, national), achieving a strong decoupling of emissions from economic growth, and limiting people’s degree of exposure to air pollutants. This implies implementing effective pollution prevention and control

policies, sustainable transport and mobility policies, stimulating investment in cleaner technologies,

promoting more sustainable agricultural methods, energy efficiency and the substitution of dirty

energy sources with cleaner ones (OECD, 2020[8]).

EU countries have set ambitious goals to reduce air pollution by 2030

Since the 1970s, the EU has been working with its member states and international organisations to improve air quality by controlling the emissions of air pollutants and integrating environmental protection requirements into the energy, transport, industrial and agricultural sectors.

In the international context, EU member states have worked since 1979 with other countries in and outside Europe to control international air pollution under the UNECE Convention on Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollution (the Air Convention), recognising that air pollution does not respect national borders. Reducing the negative impacts of air pollution is also part of the 2030 Global Agenda for Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), notably under Goal 3 (Good health and well-being) that calls for substantial reductions in the number of deaths from air pollution, under Goal 11 (Sustainable cities and communities) that aims to reduce the negative environmental impact of cities, and under Goal 13 (Combat climate change) that calls for urgent actions to combat climate change.

How can the health sector contribute to reducing the burden of air pollution?

Most policies that aim at reducing air pollution target those human activities that are its major sources – notably energy production and consumption, transportation, and the industrial and agricultural sectors. The role and involvement of the health sector in achieving air pollution reductions has to date been more limited.

The health sector can also contribute directly or more indirectly to overall efforts to reduce airpollution in at least two ways:

1. The health sector can reduce its own “ecological footprint” by improving its energy efficiency and reducing its use of various products that contribute to air pollutant emissions;

2. Public health authorities and health professionals can also encourage a transition to less polluting and more active modes of transportation through behavioural changes and promoting urban and transport policies that are more supportive of health and environmental protection.

The health sector accounts for more than 8% of GDP on average across EU countries, and its wide range of activities contribute to air pollution and climate change in various ways. The approximately 13 000 hospitals across the EU have a high demand for heating and also use a large amount of energy for their day-to-day operations and activities. Health systems also consume a lot of

medical goods and equipment that can contribute to air pollution during the production and disposal process (Health Care Without Harm Europe, 2016). It has been estimated that the health sector is responsible for 3% to 8% of the total greenhouse gas emissions in EU countries through energy consumption and the industrial production of pharmaceuticals and other medical goods (WHO, 2015).

Under the project “Health Care Without Harm”, more than 43 000 hospitals and health centres in 72 countries around the world (including in all EU countries) have already committed to reduce their environmental footprint and promote both human and environmental health through improving their supply chain through the Global Green and Healthy Hospitals initiative. Many hospitals started a long time ago to leverage their significant purchasing power to become more environmental-friendly. For example, in Vienna, public hospitals and all other public institutions are expected to consider the environmental impact of their purchasing decisions. This has led to phasing-out the use of toxic and potentially carcinogenic chemicals in disinfectants, surfaces and instruments, from four tonnes annually in 1997 to almost zero in 2014 (Health Care Without Harm Europe, 2016).

There is also great potential for hospitals and other health care facilities to achieve energy efficiency gains and reduce their reliance on fossil fuels and other dirty energy sources. In Germany, energy savings in hospitals are stimulated by the award of an “Energy Saving Hospital” quality label (Bund Für Umwelt Und Naturschutz Deutschland). In Sweden, the region of Skåne has set an ambitious goal to eliminate the use of fossil fuels in all public buildings managed by the region, including hospitals. The region was already 86% fossil fuel-free in 2016 (Health Care Without Harm Europe, 2016).

The health sector can also reduce its environmental footprint by reducing its use and waste of polluting materials and products. In many cases, the disposal of such waste involves incineration, with the potential to generate harmful emissions, ashes, nitrogen oxides, particulate matter and various volatile substances. Some hospitals in France and other countries have started to implement a comprehensive waste management policy to minimise the quantities of materials going to landfill or

incineration (Health Care Without Harm Europe, 2016).

Large amounts of food are wasted in hospitals and other health care facilities, contributing to food overproduction, additional strains on available natural resources and air pollution (OECD, 2017).

Estimates of food wasted in European hospitals range from 6% to 65% of all the food served (Williams and Walton, 2011). France has set a national objective to reduce food waste in hospitals and other collective establishments by 50% by 2025 compared with 2015, in order to reduce greenhouse gas and other emissions and avoid the unnecessary use of natural resources while reducing costs (Ministère de la transition écologique, 2020)

More broadly, public health authorities can work with other government, environmental, agricultural and industrial stakeholders to identify more effective ways to encourage both a healthy diet and more sustainable food production for the population as a whole. Results from such collaborations can be used to update nutritional guidelines to help the population make healthy choices. At the European level, the new “Farm to Fork” strategy provides a good example of a strategy designed to make food production and consumption more healthy and environment-friendly, with the aim of reducing the emission of greenhouse gases and air pollutants.

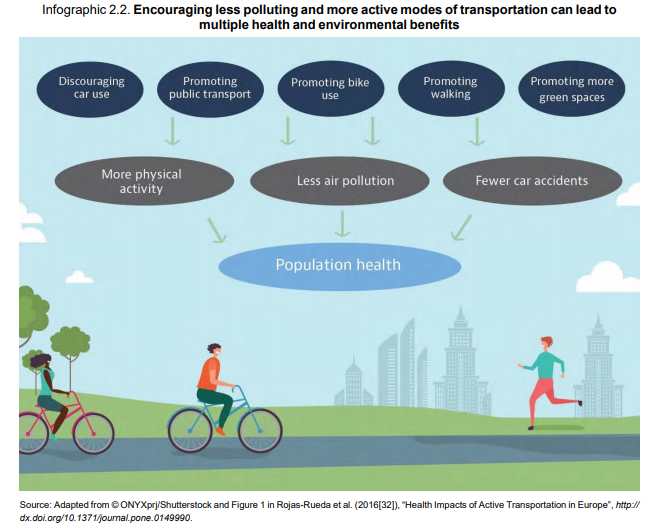

A substantial part of PM emissions and other air pollutants are due to the use of cars and other motor vehicles, which also contributes to physical inactivity, another important cause of morbidity and mortality. Public health authorities can work with other partners to encourage a transition to cleaner and more active modes of transportation, such as cycling, walking or using public transport, with benefits including less air pollution, fewer car accidents and greater physical activity (Infographic 2.2).

Health care systems can directly contribute to achieving these health and environment benefits by making adjustments to their transportation services for patients, staff and supplies. For example, over the past five years the network of public hospitals in Paris (APHP) has put in place a number of green mobility options for its staff (Health Care Without Harm Europe, 2016; European

Commission, 2020).

Since 2002, the European Mobility Week campaign has sought to improve public health and quality of life by promoting clean and sustainable urban transport. Actions during this week typically include a Car-free Day, where participating towns and cities set aside one or several areas solely for pedestrians, cyclists and public transport. Over 2 700 towns and cities across Europe participated in the European Mobility week in September 2020 under the theme of promoting zero-emission for all.

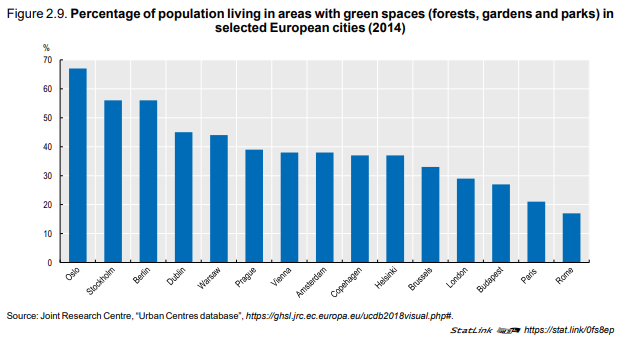

Population behaviour and the quality of air in cities are also influenced by urban design and infrastructures. Most obviously, urban sprawl encourages the use of motor vehicles and discourages more active modes of travelling (Stone et al., 2007). While urban and transport policies are beyond the usual responsibilities of public health authorities, a greater public health perspective can be brought in these policies to improve both air quality and population health. Such policies can promote a greater availability of public transportations, facilitate the use of more active modes of transportation and increase the number of green spaces.

A study covering 245 cities worldwide found that investing USD 4 per resident to increase the number of trees in a city can reduce particulate matter-related mortality by 2.7% to 8.7% (McDonald, 2016). In general, such returns on investment were found to be higher in cities with higher population density like Paris or Madrid. In Paris, it was estimated that 2.3 million people could potentially benefit from a reduction in PM2.5 by at least 1 µg/m³, at a cost of about USD 10 million per

year. The availability of green spaces varies significantly between European cities (Figure 2.9). This suggests significant potential for improvement especially in cities where this proportion is low.

Citation:

OECD/European Union (2020), Health at a Glance: Europe 2020: State of Health in the EU Cycle, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/82129230-en

One Comment

Dear author,

this is a very interesting subject to talk about. There is a need for more information for the public to become aware of their misbehaviour. To protect our nature there is much ongoing in young people, but air pollution and noise has not come into their focus.

best regards from Germany

E.R.Konsek