The practice of immunisation dates back hundreds of years. Buddhist monks drank snake venom to confer immunity to snake bite and variolation (smearing of a skin tear with cowpox to confer immunity to smallpox) was practiced in 17th century China. Edward Jenner is considered the founder of vaccinology in the West in 1796, after he inoculated a 13 year-old-boy with vaccinia virus (cowpox), and demonstrated immunity to smallpox. In 1798, the first smallpox vaccine was developed.

Over the 18th and 19th centuries, systematic implementation of mass smallpox immunisation culminated in its global eradication in 1979. Louis Pasteur’s experiments spearheaded the development of live attenuated cholera vaccine and inactivated anthrax vaccine in humans (1897 and 1904, respectively). Plague vaccine was also invented in the late 19th Century. Between 1890 and 1950, bacterial vaccine development proliferated, including the Bacillis-Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccination, which is still in use today.

In 1923, Alexander Glenny perfected a method to inactivate tetanus toxin with formaldehyde. The same method was used to develop a vaccine against diphtheria in 1926. Pertussis vaccine development took considerably longer, with a whole cell vaccine first licensed for use in the US in 1948.

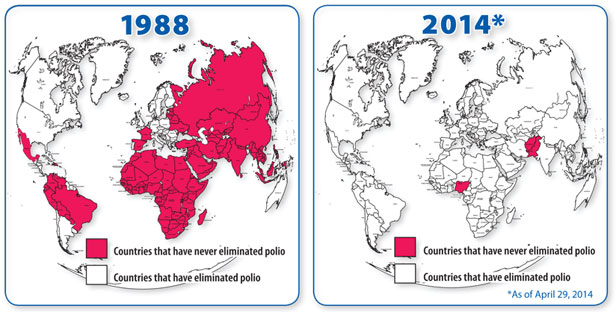

Viral tissue culture methods developed from 1950-1985, and led to the advent of the Salk (inactivated) polio vaccine and the Sabin (live attenuated oral) polio vaccine. Mass polio immunisation has now eradicated the disease from many regions around the world

Immunisation is the most effective way to actively protect your child from preventable diseases, such as whooping cough, tetanus, hepatitis B and measles.

The first time we are exposed to a germ, for example a bacterium or virus, it takes time for the immune system to respond and we become unwell. However, once the immune system has memory of the infection, it is able to respond rapidly to destroy the germ the next time we are exposed.

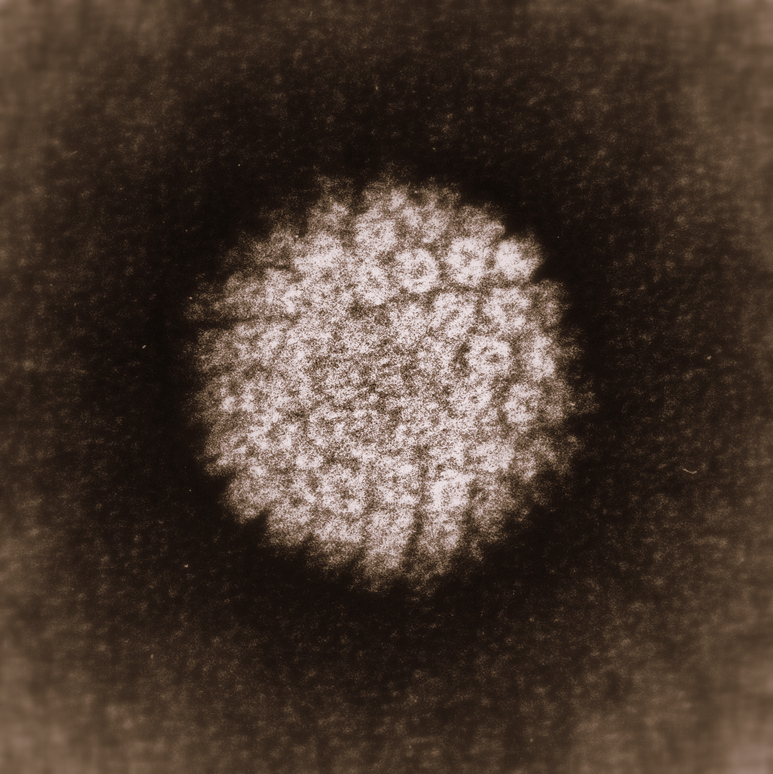

Vaccines contain parts of or weakened versions (inactivated or attenuated) of a particular germ. Vaccination exposes the body to parts of the germ for the first time without causing disease, and subsequently, the real germ can be rapidly destroyed if it enters the body to prevent illness.

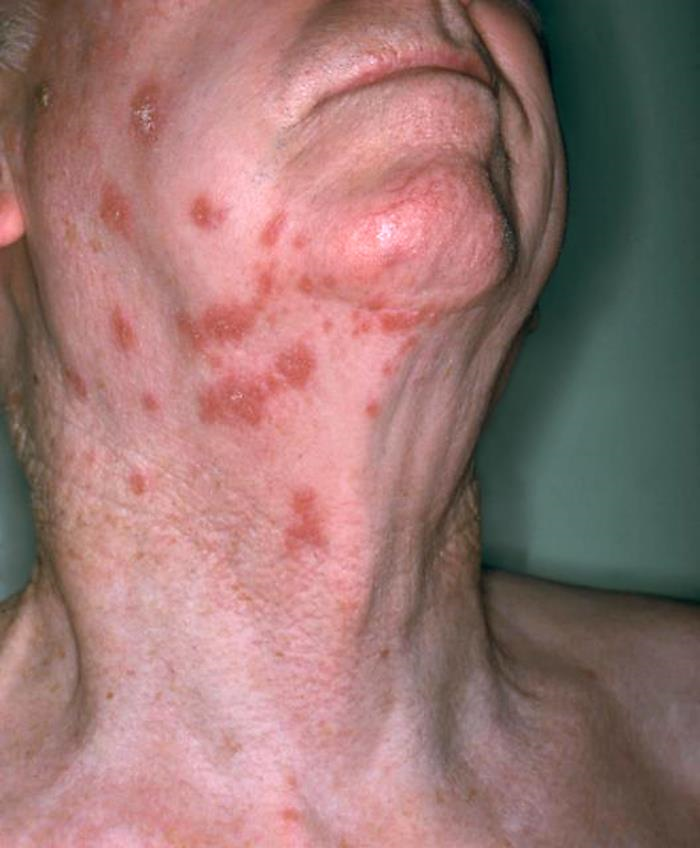

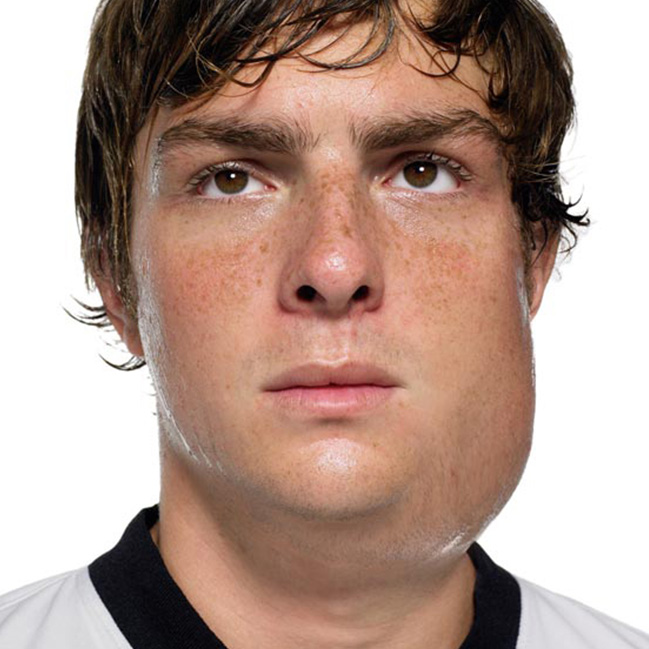

Very young children are particularly at risk of becoming sick, because their immune system lacks experience and is unable to respond quickly. Many of the diseases that vaccines protect us from are very serious in young children. Some, for example measles, are highly contagious and usually fairly mild, but pose a risk of serious complications even in healthy people. Immunisation is the safest and most effective way to provide protection for your child’s health.

The National Immunisation Schedule provides the best protection for our children when they are most at risk. From six weeks of age, children can be protected from several potentially dangerous diseases. It is very important to stick to the schedule – not immunising your child increases the risk of them getting the infection, and not keeping up to date reduces the protection that the immunisation can provide. It takes a few months and repeated doses of a vaccine for an infant to be fully protected.

MÜTTER MUSEUM

The College of Physicians of Philadelphia

Published in GI-Mail 10/2022 (English edition).

- Do you already know our monthly newsletter GI-Mail with useful tips on postgraduate courses?

Sign up here. - Are you looking for vacancies or new career challenges? Here you will find the latest vacancies and job offers.

- Do you already know our monthly job-information GI-Jobs with current job offers for doctors, managers and nurses? Sign up here.

- Are you interested in up to date postgraduate courses and CME? In our education database »medicine & health« you will find new education events from over 2300 organizers.